Disclaimer: Zahra Schenck is a former Diamondback copy editor.

Senior economics major Zahra Schenck needed a science credit that wouldn’t tank her GPA.

With graduation looming, she was in search of a natural science lab that would fulfill her last requirements — but spare her from chemistry or physics, she said.

She stumbled upon astronomy principal lecturer Melissa Hayes-Gehrke’s astronomy course and enrolled in it last spring.

“I just thought, ‘Okay, planets are cool,’” Schenck said. “I didn’t fully know what I was getting into.”

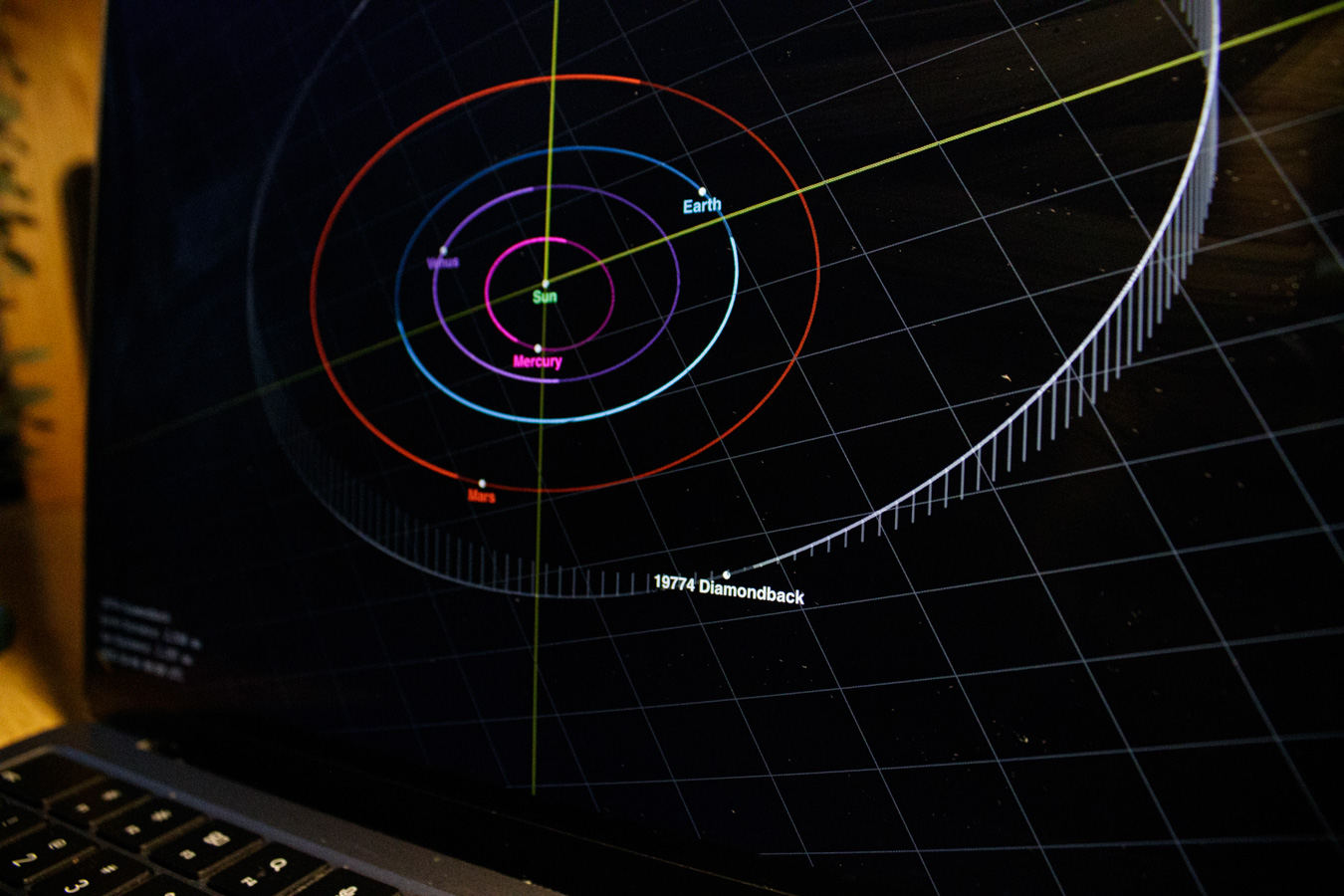

By the end of that semester, she and 11 other students published scientific findings about the physical properties of an asteroid between Mars and Jupiter, which they later named “Diamondback.”

Students in Hayes-Gehrke’s class observe an asteroid and publish research in the scientific journal Minor Planet Bulletin. “There are very few university courses in the world that offer this opportunity,” the class syllabus reads.

[UMD STEM students worry about impact of AI, federal workforce cuts on job market]

Hayes-Gehrke said the opportunity to publish research is exactly what sets the class apart.

“Students love that they’re actually doing something new,” she said. “Usually in classes, you feel like there’s busy work, and you get to some result, but you feel like the result was already predetermined.”

The opportunity proved invaluable for students such as CC Lizas, who was on Schenck’s team.

“I didn’t do other science stuff at all,” the senior philosophy, politics and economics major said. “I just was so excited to have the chance to do this.”

Schenck, Lizas and their team members remotely controlled a telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in Australia to track the asteroid. They took images of the asteroid using online software and recorded its brightness over time to track its movement in the solar system.

Schenck and her teammates completed their research last spring despite technical problems and weather-related setbacks. Their findings were published in the Minor Planet Bulletin in late September, according to a computer, mathematical and natural sciences college news release.

[3 UMD grants among $7.5B in Department of Energy cuts nationwide]

Schenck and Lizas both said their biggest takeaways came from working together.

Hayes-Gehrke mixed students into teams with different majors, including philosophy, computer science, economics and government. This allowed them to lean on each other’s strengths, Lizas said.

“The whole class is a group project,” Lizas said. “We were all learning so much from each other because we did have these different backgrounds.”

According to Lizas, the diverse makeup of teams was intentional. Teams were carefully constructed based on surveys to ensure diverse expertise, she said.

Hayes-Gehrke said she designed the class around collaboration. The amount of data students collect throughout the asteroid-tracking process would be overwhelming to sift through individually, she said.

The teams faced one more decision after completing their observations: what to officially name their asteroid that previously carried the temporary name “2000 OS51.”

[UMD TerpAI updates aim to boost campus adoption]

Following the precedent of another team in Hayes-Gehrke’s previous classes that named an asteroid “Testudo” in 2024, the team wanted another university-related name, Schenck said.

Schenck said her team chose “Diamondback” because they believed many students at the university would connect with it.

For Schenck, now a finance graduate student at this university, the teamwork skills she gained while tracking the “Diamondback” asteroid were immediately applicable.

“You need to be able to communicate and also collaborate within your own team to get stuff done,” she said. “Those sorts of lessons were more important to me.”

Lizas, who is studying abroad in Copenhagen this semester, said a class she thought would simply help fulfill her science requirement ended up exceeding expectations.

“It was the perfect class,” she said. “It really was.”